Speaking of upgrade pricing…

Will I be able to pay for an upgrade from Version 1.x to Version 2.0?

No. To update your app to the latest version, please purchase an Update Pass, or purchase the latest one-time purchase version of the app (Version 2.0).

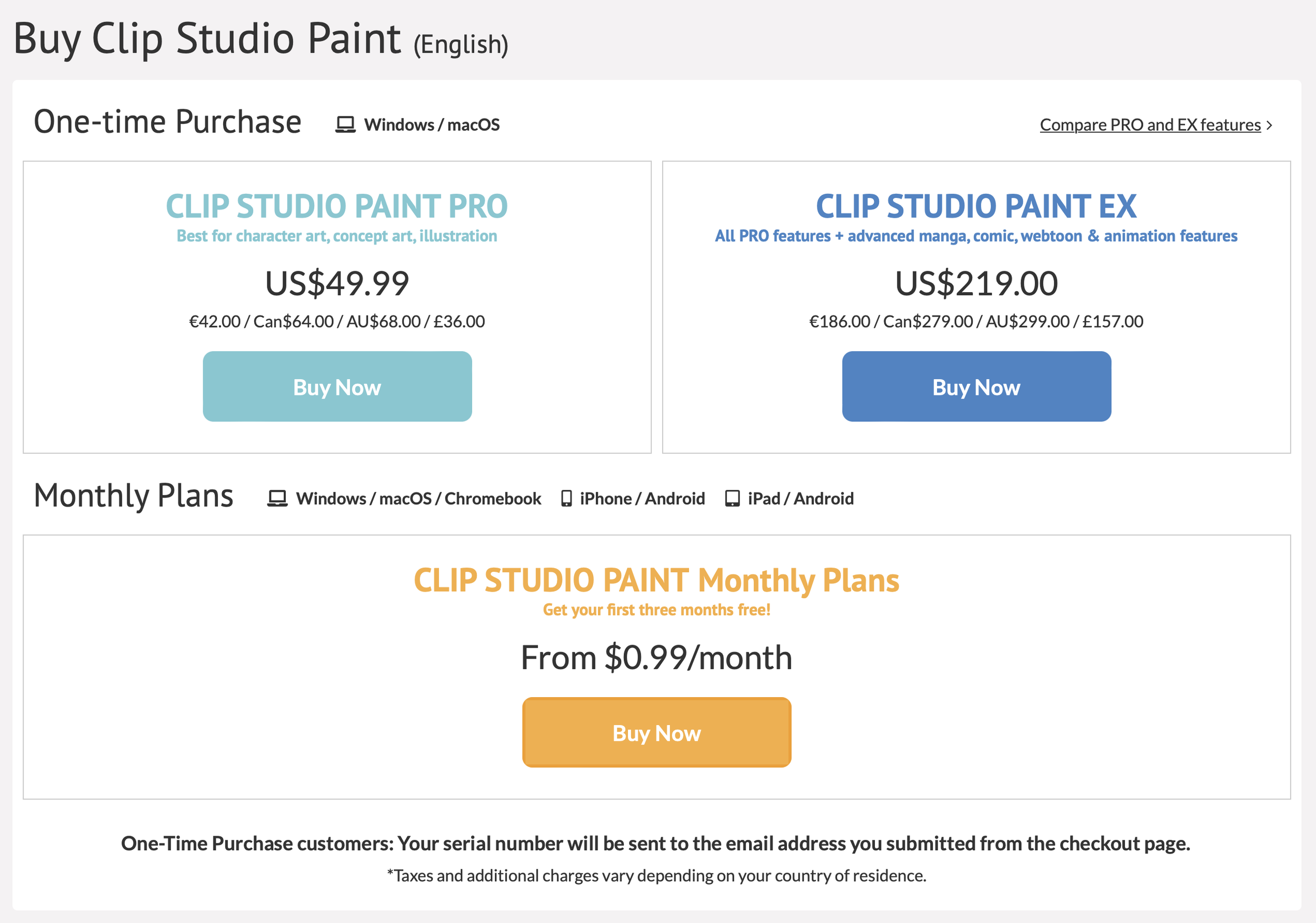

Again, this is a bad answer to this question! What they’re trying to say is that there is no special upgrade pricing for version 2.X. If you own a perpetual license for 1.X, you will need to buy a brand new perpetual license for 2.X at full price. Or wait for it to go on sale, but still. Owning 1.X gives you no special benefits when it comes time to buy 2.X.

Will I still get free bug fixes for the perpetual version?

Yes. The perpetual version will still get free stability updates when necessary to address major bugs in the app. Version 1.x will be supported in this way until Version 3.0 is released in the future. Moving forward we will provide this support for the current and previous major version of the app. So, until Version 3.0 is released, Version 1.x will continue to receive stability updates. However, even after support is discontinued, you are still free to use the permanent license of Version 1.x for as long as you like, provided your device and OS can run it.

What this means is that if you have Version 2.X and let your update pass expire, you will still receive new stability/bugfix patches, but not further feature updates. Version 1.X will also receive maintenance/bugfix patches until the release of version 3.0. After version 3.0’s release, version 2.X will continue to get maintenance/bugfix patches, and so on.

Will I still be able to get free feature updates as I do now?

New features for the perpetual version will be included in each major version (2.0, 3.0, etc.), however, new feature updates will not be provided free of charge. Even if you have purchased the perpetual version of Version 2.0, you will still need to purchase an Update Pass in order to get access to new feature updates. If you are a Monthly Usage Plan or Update Pass customer, you will receive access to new feature updates (2.1, 2.2, 3.1, 3.2, etc.) as they become available for no extra charge.

The feature update train is over without an update pass. 1.x will get no more feature updates after 2.0 is released (I think, more on that in a second), and if you’re on 2.0 you need to pony up for an update pass to get feature updates. However, this doesn’t answer a critical question: what happens to the feature updates you paid for when your update pass expires?

The Maintenance License Model of Software

“What happens when I stop paying for update passes?” is a very important question that the flowchart tries to answer but fails to do so in an extremely awful way. For decades most software was sold under a “Buy a major version, then pay slightly less money for an upgrade version later on” model. Then software subscriptions came along, which demanded monthly payments while holding your programs (and therefore your work) ransom if you stopped paying. But these aren’t the only ways of paying for software. Even most “free as in speech” software is bound to some form of license, like the GNU Public License or BSD License. Unless the software is in the public domain, it’s under some form of copyright, and copyright means a license gets involved sooner or later. In the realm of commercial software, there’s a lot of ways to pay for a license. Freeware, shareware, nagware, subscription, perpetual with forever updates, perpetual with minor updates, or even time-limited that expires after a one-time fee.

Most people are used to buying software at retail (even if retail means a website or app store). Outside the world of retail software, there’s many ways to sell a license. Dongles are still a thing, acting as physical keys for niche and expensive software. Another method popular in enterprise software is the maintenance license model. Different companies might call it by different names—software assurance, update guarantees, whatever—but the idea’s pretty straightforward. You buy the software, and then you pay a quarterly/yearly/some number of years for a maintenance license. The vast majority of these products work on a date entitlement system, where your license key works on versions released up to a certain date.

Let’s take a very popular example: VMWare. You can buy the cheapest VMWare package, vSphere Essentials, for a very reasonable price. It’s great for small shops that aren’t running multiple huge clusters but still need to run several virtual machines on up to three nodes. When you buy vSphere Essentials, you’re presented with two purchase options: a one year or three year software support term. vSphere itself is perpetually licensed under this model, meaning that when you buy it, the server software won’t expire or stop working at an arbitrary date. Rather, the support terms are for how long you’re entitled to major new versions of vSphere.

So if I buy vSphere essentials with a one year support agreement, it means that I’m entitled to all new versions of ESXi and vCenter for one year. When I purchased the app, version 7.1 was the current version. Six months later, version 7.2 is released, and I’m good to run version 7.2 forever. But another seven months go by and version 7.5 is released. I’m out of luck—its release date is after the expiration of my support agreement. Version 7.5 will refuse to run without the new license key from VMWare’s software support. A package with a one year agreement costs around $575, while the three year agreement is around $686. I bet most people opt for the three-year upgrade support option. Regardless, your VMware host doesn’t turn into a pumpkin after that update support expires. VMWare is also good about releasing patches or update rollups for older point releases, and those aren’t bound by that time limit—at least, they weren’t when I was administrating VMWare.

I worked for companies that used this same kind of structure, except we called it an “annual maintenance license” or “service contract.” Those agreements usually included technical support in addition to software updates, but the idea is to have the customer pay for the ongoing development of the software without threatening them with a deactivation if they stop. At one company we sold “major” versions with point releases included in the service agreement. For example, you’d pay $5,000 to upgrade to version 12.0, and you paid $1,750 yearly to get access to any point releases in that major version. You could decline to renew your support contract the next year, and your software would continue to work, but we’d stop mailing you new software update disks. Another company I worked for used the same method, except they didn’t charge for “major” versions and had a more expensive annual maintenance license. That AML meant you could run any version released up to AML’s expiration date. Once it expired, your software would continue to work, but the installers for new versions would bark and say “Hey! Your AML is out of date, you can’t install this.”

I believe this is the model that Celsys is moving to with Clip Studio. It makes the most sense from a “you get what you pay for” standpoint. If I pay for version 2.0 and it comes with a one year update pass, I expect that whatever version comes out at the end of that pass—let’s say, 2.2—will continue working after the update pass expires. You would also get the bugfix/maintenance releases for 2.2 afterwards even without an update pass. The alternative—forcing you back to version 2.0—is so pants-on-head stupid that I can’t believe it would happen, but Celsys’ communication is so bad that I can’t rule it out completely.

A Masterclass in Torching Goodwill

With how confusing their FAQ was and the even more baffling flowchart, Twitter and Reddit naturally went nuts. Celsys bought themselves a lot of goodwill over the past few years with their update policy for CSP 1.X, and it’s all gone up in smoke because people are assuming the worst. I don’t blame users for those assumptions—Adobe, Avid, and other companies have become software landlords that grew fat off the back of subscription revenues. Celsys took advantage of growing anti-Adobe sentiment and positioned Clip Studio as not just a better product than Photoshop for comics and illustration, but that they were a better company. Well, time’s up on that. Celsys had their chance to properly explain things, and they blew it.

Celsys is a Japanese company; they’re not in America let alone Silicon Valley. The kinds of market pressures that are exerted on American companies are different than Japanese ones. But at the end of the day, revenue in must be greater than expenses out, and I’m not surprised that version 2.0 is seeing changes to the licensing model. “Free updates forever” is always too good to be true. I’m sure the suits at Celsys knew there would be some backlash to this, but the backlash is worse than it should have been because their announcement was terrible. Even if they come out and clarify things, they will have irrevocably lost some users, especially vocal fans.

The reality is that software development costs money. It’s entirely Celsys’ own fault for the situation they’re in, and update passes are absolutely a way to wring more money out of people. But I’m not immediately opposed to this kind of licensing scheme, especially if it just means “Oh, I can buy an update pass once in a while when I feel like I need it.” The software will still work, I can still get work done, and I can get on with my life. After all, I charge royalties and licensing fees for my photographs—I know the struggle. I also work for a software company for my day job, so I’m intimately familiar with cost structures and the problem with ongoing revenue. Products cost time and money to maintain, and no piece of software lives forever. But it’s monumentally stupid to announce this change without also giving people an idea on pricing and how many feature updates are expected per year, let alone how many bugfixes will come for each release.

So if people wanted to switch, where would they go?

Adobe isn’t really an option. Photoshop is pure subscription, it’s more expensive than Clip Studio, and it’s missing a lot of features that CSP users love.

“Well, I’ll just switch to Serif!” you say, and fair enough, but keep in mind that while Serif sells perpetual licenses for the Affinity suite, they are working in a “major versions require a paid upgrade” model. All of their updates to date have been “minor” or feature upgrades, so they have yet to charge for an update. But a day will come when they release 2.X, and that will be a paid upgrade. I doubt it’ll be full price if you own the current version, but it’s only a matter of when, not if. So don’t get mad when 2.0 comes out and it costs money to upgrade. The Affinity Suite is a good Photoshop/Illustrator/InDesign fighter, but it’s not a suitable replacement for CSP.

Krita is free and open source, and while it’s gotten better over time, it’s still not as good as CSP. Still, it’s very usable and has an excellent community. It’s worth an evaluation, at least. For now, I’d stay put until pricing details come out and Celsys clarifies how feature updates interact with Update Passes.

There’s always Paint Shop Pro, I guess. But we all know that’s not a serious option.

Storyboard Pro, Sketchbook Pro, and other options might fulfill other users’ needs, but their licensing schemes aren’t much better than Adobe’s or the proposed one for Clip Studio.

Writing a better FAQ

I commend you on making it through all that. Celsys really stepped in it this time, and their confusing FAQ is part for the course with communications from these Japanese development houses. This was an entirely self-inflicted wound that could have been avoided with better communication on their part. At the end of the day, what they’re proposing isn’t a subscription like Adobe, it’s a maintenance plan for a perpetually licensed piece of software. It won’t explode if you stop paying, which is the real problem with Adobe’s subscription plan. In fact, I’ve seen this very idea for a perpetual license with optional maintenance put forward by people who use Adobe software! So whether this is a dealbreaker or just the cost of doing business is subjective. I paid for CSP ages ago and use it infrequently. I’ll probably hang on to 1.x and upgrade to 2.x when it’s on sale. I doubt I’ll buy update passes regularly.

If I was on Celsys’ team, here’s the plan I would have devised for their new perpetual licenses.

First, Clip Studio 1.x would stop getting feature updates upon the release of 2.0. Maintenance (bugfixes) would carry on until the release of 3.0, whenever that may be. There would be no update passes for 1.x.

When users buy version 2.0, they get one or two years of update passes included in the price. You are entitled to whatever feature releases come out during your Update Pass(es). After the update passes expire, whatever version was the last one before the expiration date continues to run. You are entitled to any maintenance/minor bugfix releases to that version as well. If you buy another update pass, you’re now clear to get updates again until the pass expires, at which point your latest version is the one you keep.

When version 3.0 comes out, rinse and repeat the process for 2.0.

This is the sanest, simplest way to do what Celsys wants to do. It’ll still piss some people off who thought they were getting updates for CSP for eternity, but as far as update service agreements go, it’s pretty tame and pretty balanced in terms of user need / development cost. And until we actually know how much update passes and version 2.0 costs, we’re all just kind of spitballing here.

As far as communicating to customers, here’s an FAQ that would actually answer relevant questions.

I own Clip Studio 1.x. What does this mean for me? Clip Studio 1.X perpetual licenses will continue to work! After the release of Clip Studio 2.0, version 1.X will receive no further feature updates. Bugfix/maintenance patches for version 1.x will continue until the release of Clip Studio 3.0, at which point support for version 1.X will be discontinued.

Can I upgrade to Clip Studio 2.0 for a reduced price? No. You must purchase a new perpetual license for Clip Studio 2.0 if you are an existing owner of Clip Studio 1.x.

When my Update Pass expires, what happens to my current version of software? You can run the latest feature version of Clip Studio Paint that was released before your Update Pass expired. For example, if CSP 2.2 came out on August 17, 2022, and your Update Pass expired on August 22, you can still run CSP 2.2 perpetually. However, if Clip Studio 2.3 came out on September 22, 2022, you would not be able to run version 2.3 without purchasing another Update Pass.

What about bugfix (X.X.1) releases? Even if your update pass is expired, you are entitled to bugfix releases for your version of CSP. For example, if you are licensed for version 2.2, then you would be eligible for versions 2.2.1, 2.2.2, and so on.

Can version 1.X open files created in version 2.X? Yes. However, some features may not be available. These limitations will be announced at a later date.

Will anything change for monthly or yearly subscription users? Nope! You’ll always receive the latest version as long as you have an active subscription.

If Celsys is reading this (highly unlikely), you can still clarify things and simplify your licensing arrangements. Make it clear that this is not a subscription, and that people’s software will still work when Update Passes expire. Don’t offer update passes for version 1.X. Offer a cheaper upgrade option for 1.x users to get a 2.x perpetual license. That would be enough to cool people’s jets and clear the air.

Let’s hope Celsys clears the air. I don’t work for them, so my interpretations could be wrong. But given my experience in working for software companies, I’m pretty confident in what’s actually happening. Also, a few apologies wouldn’t hurt. I’ll be sure to update this in the future when more clarifications come from Celsys.